The Kitemare

Our main nemesis Gosh flying their Code 1

The spinnaker is the largest sail we fly in front of the boat when we’re sailing downwind in what sailors optimistically refer to as “moderate conditions.” It’s essentially a kite—if your childhood kite had the power to rearrange your facial features. We carry three of them. The Code One is 130 square meters, roughly the size of our apartment, and made of material so light it feels illegal, like parachute silk designed for people who don’t plan on landing. The Code Two is not much smaller but considerably tougher, meant for stronger winds. Of all the spinnakers, it is the workhorse, which is to say the one most likely to kill you through exhaustion rather than sudden violence. The Code Three is smaller still and made of sturdy sailcloth, presumably for people who prefer their danger in manageable doses.

The spinnaker is attached to the boat in a way that sounds simple until you see it in action. The front is secured with a tackline, the top with a halyard, and the back corner—the clew—with two sheets used to trim the sail. “Trim” is a polite word meaning prevent it from destroying everything. The spinnaker is a deeply temperamental sail and demands constant attention, like a spoiled child with a grudge. The sheets, in particular, are unpredictable and enjoy lashing out at crew members, aiming for the face, the arms, or any exposed body part that looks emotionally vulnerable.

Bob taking it easy while trimming

To keep the sail from collapsing or launching us into another time zone, it must be trimmed constantly—eased out or pulled in. This is accompanied by the commands “Ease,” meaning let it out before it kills us, and “Grind,” meaning pull it back in before it kills us. The trimmer sits on the high side of the boat, clutching the spinnaker sheet and staring at the sail with the intensity of someone defusing a bomb in a movie. He watches for signs of imminent collapse, at which point he or the helm yells “Grind” at the grinder, who is stationed at the primary winch, also known as the coffee grinder, because it requires about the same motion and produces the same sense of despair.

Lisa and Sarah grinding the Yankee

The grinder hauls in the sheet until someone yells “Hold,” at which point he must stop immediately, regardless of what his arms are doing or how attached they feel to his body. Then comes “Ease,” and the sail is let out again until it is hovering just shy of total failure. This cycle continues endlessly, day and night, like a very specialized form of cardio.

One night, while our watch was off, we were woken by the words every sailor dreads: “ALL HANDS ON DECK.” This means you exit your bunk at record speed, dress badly, and stumble on deck convinced that whatever is happening is both urgent and somehow your fault. The spinnaker’s tack had come loose and slipped under the boat, dragging the sail with it. At the same time, a squall blew in with more wind than the sail—or our nerves—could handle.

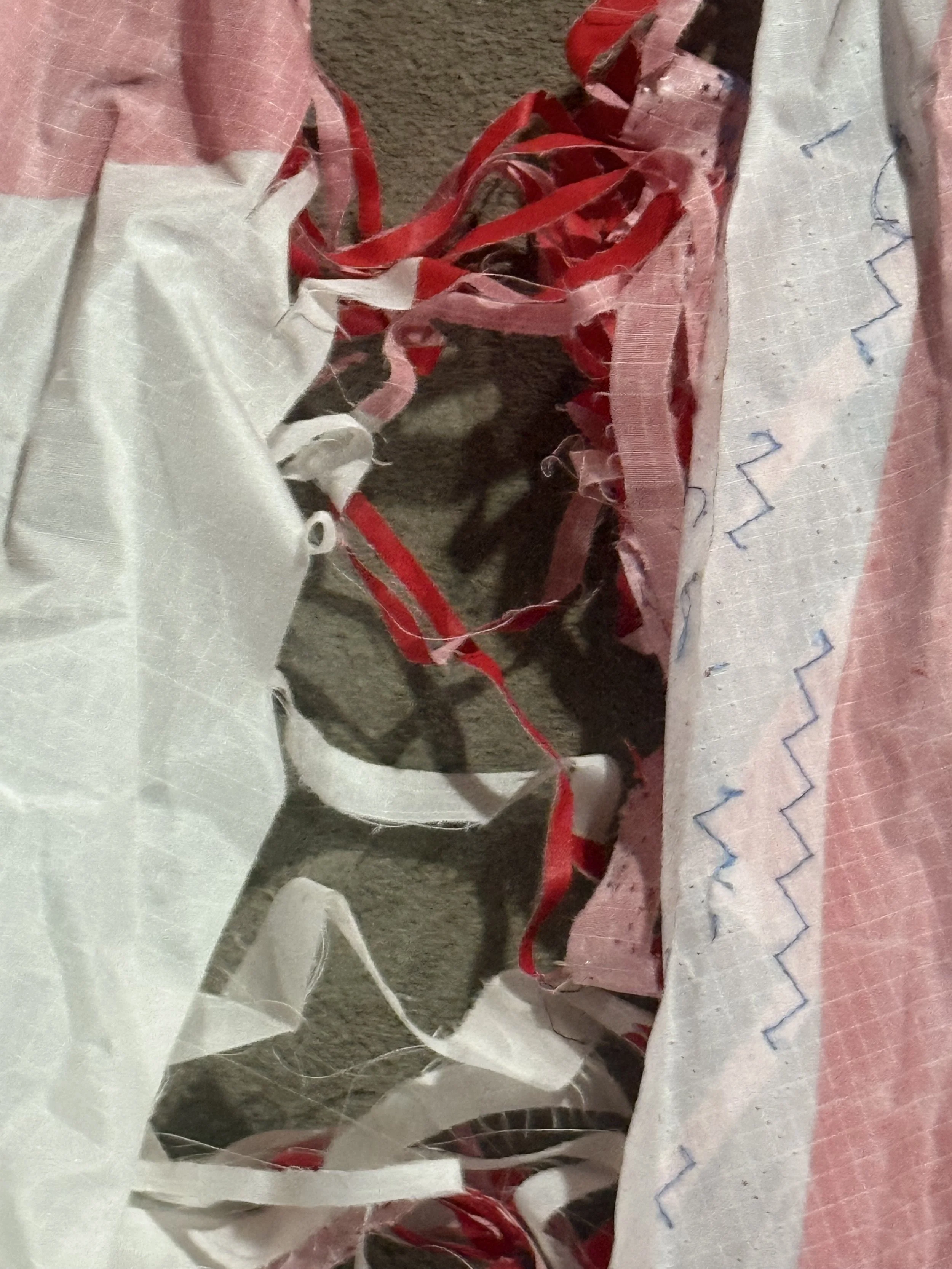

The other watch was trying to get the sail down, while our first mate, Zoe, was in the water in a drysuit, attempting to figure out where the sail was tangled. This struck me as heroic, though I personally would have preferred a dry couch and several locked doors. Eventually, we managed to pull the spinnaker down, revealing a large shredded hole in the middle and a three-meter rip running the length of it, like a lightning bolt designed by someone with anger issues.

For a more precise and competent account of what happened, I recommend Bob’s Blog, where the sequence of events is explained by someone who understands them. In the following days, we took photos of the damage to send to Hyde, the sailmaker, and began repairs onboard—carefully, reverently, and with the knowledge that this sail would one day try to kill us again.